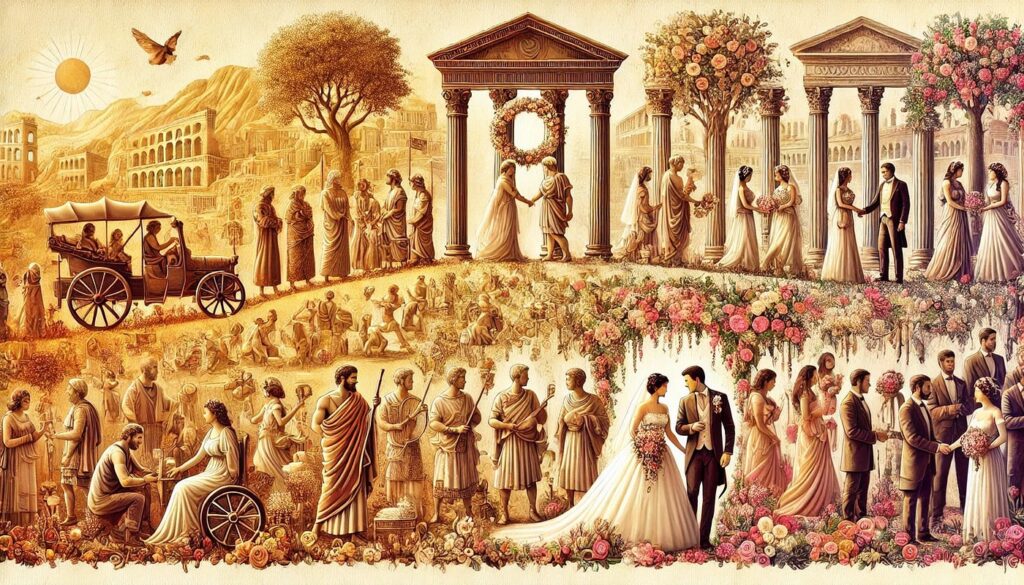

Examining the evolution of monogamy through a “follow the money” lens opens up a fascinating look into how societal norms, economic incentives, and unseen powers might have shaped one of humanity’s oldest social institutions. Though monogamy is often closely linked to religious values, especially in the modern West, history reveals a far more varied backdrop, with many early societies embracing various forms of polyamory, polygyny, and group marriage. The emergence of monogamy as a cultural standard hints at forces beyond mere societal preference—possibly influenced by entities with vested interests in its economic and social structure.

Historical Context: Monogamy and Polyamory in Ancient Cultures

Early Mesopotamian records, such as the Code of Ur-Nammu (2100–2050 BCE) and the Code of Hammurabi (circa 1754 BCE), allowed for polygamous marriages among wealthy men, establishing marriage not only as a partnership but also as a tool for consolidating power and wealth within families. Legal structures began to recognize and regulate marital relationships, yet monogamy was not enforced as the exclusive marital standard.

Religious and cultural documents reveal that monogamy was not the initial norm for human societies. Many ancient civilizations, including those in Mesopotamia, Egypt, and parts of Asia, recognized and even endorsed forms of polyamory. It was common for leaders, aristocrats, and even entire communities to practice forms of polygamy or polyandry, while monogamy evolved as a gradual preference for the masses. Ancient religions, often thought to emphasize monogamy, also show polyamorous practices woven into their origins. For instance, biblical figures in the Old Testament, such as Abraham, David, and Solomon, had multiple wives or concubines.

The Romans practiced a mix of monogamous and polygamous unions, though Roman law generally promoted monogamy, partly to streamline inheritance and simplify property rights. However, infidelity was culturally common, especially among the elite, and adultery became profitable, with fines and public shaming as punishments (Gardner, J., Women in Roman Law & Society, 1986). Despite its ideals, this era demonstrates how monogamy still fostered a parallel economy around marital transgressions.

The Shift to Monogamy: Societal Control and Economic Ties?

As societies transitioned from hunter-gatherer lifestyles to agrarian economies, stable partnerships became more desirable. This was likely influenced by practicalities—managing land, resources, and inheritance across large groups posed challenges. Thus, monogamous unions, at least superficially, were favored to stabilize property and family lineages. However, this shift also came with societal control, as ruling classes encouraged exclusive pairings to consolidate wealth and power.

The Catholic Church formally sanctioned marriage as a sacrament and reinforced monogamous unions. This shift, while religious, had socio-economic implications. Enforcing monogamy incentivized families to maintain singular, orderly inheritance lines, which stabilized church donations and facilitated property transfers (MacCulloch, D., A History of Christianity, 2009). The Church profited through fees for marriage sacraments, annulments, and indulgences, bolstering its wealth and societal control.

With time, monogamy became more than a preference; it was enforced through religious laws, cultural expectations, and legal systems. The nuclear family unit gained prominence as society transitioned to an industrial model. Monogamy became the societal norm among the middle class, tied to factory labor schedules and predictable family arrangements. Legal firms specializing in family law flourished as divorce became more accessible, with a 1970s-era spike in the U.S. and Europe marking the dawn of “divorce profiteering” (Cherlin, A., Marriage, Divorce, Remarriage, 1981).

The economic motivations are clear here: with stable family units came predictable inheritance patterns, tax benefits, and increased control over populations. This consolidation was profitable for emerging institutions like religious organizations, which received donations and support from families bound by monogamous relationships. Laws and societal expectations reinforced these practices, setting a lucrative foundation ripe for further exploitation in later centuries.

The Economic Complex Around Monogamy

As monogamy became enshrined in the societal fabric, a multi-industry network thrived on marriage and its promises. Industries that benefit directly include:

- Legal and Court Systems: Divorce litigation, prenups, child custody battles, and property divisions create a reliable income stream. These industries particularly benefit from the “impossible expectation” aspect of lifelong monogamy in a high-divorce culture.

- Retail and Jewelry Markets: With the symbolic importance placed on marriage and monogamy, wedding rings, engagement jewelry, and bridal wear become mandatory purchases in many cultures, generating significant profits.

- Real Estate and Housing: Monogamous unions and subsequent nuclear families often need separate housing units, generating demand for suburban homes and driving real estate markets.

- Entertainment and Hospitality: Honeymoons, anniversary celebrations, and “date nights” all tie into the economy of love, catering to the expectations of a monogamous lifestyle.

Following the Money: A Conspiracy Theory?

Tracing the money involved in promoting monogamy reveals an intricate network where various industries benefit handsomely from the societal pressure to conform to monogamous ideals. But are there high-level intelligence forces or institutions purposefully promoting this structure?

One could hypothesize that financial interests from influential groups within religious institutions, corporations, and even early governments saw monogamy as a tool for societal stability and a profit-making opportunity. Institutions like the Catholic Church, for example, historically enforced monogamy in ways that expanded their influence and, by extension, their wealth. This established precedent shows a pattern where controlling relationships, property, and family structure leads to control over society at large.

Modern Profit Motive: Monogamy as Big Business

Today, monogamy continues to be immensely profitable. The pressures for weddings, home ownership, luxury vacations, and ongoing “relationship maintenance” add up to trillions in consumer spending globally. By analyzing revenue streams, one might speculate that marketing campaigns, media, and governmental policies encourage monogamy, presenting it as an aspirational ideal and a baseline expectation. This could indicate a deliberate strategy by powerful institutions that profit from monogamous structures that remain the default.

A Logical Conclusion?

The suggestion of high-level intelligence forces beyond governments profiting from monogamy is speculative but not unthinkable, especially given historical examples of ideological or economic influences exerted by powerful groups. Though evidence linking shadow entities directly to the establishment of monogamy is hard to substantiate, the economic web surrounding it is undeniable. By “following the money,” we see that monogamy’s persistence, despite high divorce rates and personal dissatisfaction in some cases, serves as a testament to its enduring profitability.

One would need access to records linking lobbyists, policymakers, and corporate interests with religious and legal institutions to trace these connections further. Although no “smoking gun” proves a single high-level conspiracy, the array of industries benefitting from monogamy’s challenges and expenses strongly suggests that societal structures and expectations may not merely be about personal choice but a large-scale economic engine.

The Business of Monogamy’s Instability: Infidelity and Temptation Economics

The profitability of monogamy’s “instability” comes largely from industries capitalizing on the appeal of infidelity, thrill-seeking in relationships, and marriage’s perceived exclusivity:

- Dating Apps and Infidelity Sites: Platforms like Ashley Madison, which reported $100 million in revenue in 2018, demonstrate how catering to infidelity is a booming market. By normalizing extramarital affairs under a veil of anonymity, such businesses tap into individuals’ curiosity and temptation (Fleming, M., “Data from Infidelity Sites,” 2019).

- Family Law Firms: Divorce lawyers in the United States earned approximately $11 billion in revenue in 2019 alone (IBISWorld, U.S. Divorce Lawyers Market Report, 2019). Non-monogamists and infidelity play significant roles in these cases, as breaches in trust prompt separations. Legal firms, alongside courts and counseling services, thus profit from monogamy’s challenges by charging substantial fees for divorces, child custody battles, and alimony settlements.

- Therapy and Couples Counseling: Marriage and couples counseling is a billion-dollar industry in the U.S., with infidelity a common issue brought to therapists. With hourly fees averaging $75-$150, therapy for individuals grappling with marital dissatisfaction or betrayal highlights another profitable sector reliant on monogamy’s fragile stability (American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy, AAMFT Statistics, 2020).

- Entertainment and Media: Shows like The Affair and films focused on adultery romanticize infidelity, catering to both monogamous and non-monogamous viewers. This focus, combined with the success of dating reality shows where contestants tempt committed individuals, indicates a multimillion-dollar industry centered on the appeal of infidelity.

- Private Investigation Services: The PI industry, valued at $5 billion in the U.S., often serves clients seeking to confirm suspicions of cheating, emphasizing the cost individuals are willing to pay to address fears related to monogamy’s potential instability (Statista, Private Investigation Market Revenue, 2020).

A Logical Conclusion: Power and Profit Beyond the Surface?

By following the money, we find that monogamy, though presented as a societal ideal, serves as a cash flow mechanism benefiting numerous industries. Historical shifts underscore that while monogamy may offer social stability, it is also engineered to yield considerable profit for those positioned to exploit its inherent challenges, from religious institutions in medieval Europe to modern-day legal and entertainment industries.

The potential for unseen entities or powerful organizations with financial incentives to support and sustain monogamy remains speculative yet plausible. By cultivating societal norms around monogamy and subtly promoting an “impossible expectation,” industries that thrive on stability and breaches in that stability will likely continue to benefit—ensuring a future where the promise of exclusivity and the temptation to break it remains central to the economy.